Tool Time!

Over the course of a lifetime managing my family’s forestlands, I’ve learned a lot about the value of having the right tools for the job, and bringing them along each time I go to the woods. I have to admit that a strange voice lives in my head which frequently tries to convince me I’ll need fewer tools than I think for a particular trip. Inevitably, however, whenever I skimp on my tool inventory, I come to a point in a project where a missing tool prevents me from proceeding. I’ve taken to making a list of tools and materials the day before a trip to one of our family’s forests, which helps stanch that voice and better prepare for a weekend of tinkering. I’m also fortunate to have a wife who knows a lot about both tools and my decision-making habits, who never allows me to leave home without at least two chainsaws and a come-along.

I’ve shared below a list of tools and equipment that I use most often throughout the year, their approximate costs, and commentary on my experience with them. The tool and equipment brands listed below do not constitute an endorsement of those brands by either the author or the Northwest Natural Resource Group; what’s more, my opinions about each of the tools below are likely to change day to day.

ATV

Let’s start with my favorite toy tool. A few years ago, I purchased an ATV as a multi-purpose vehicle to get my gear into places on our land that are inaccessible by truck. The ATV is a very nimble machine for carrying saws and/or planting tools directly to a worksite deeper in the woods. I chose a CFMoto 600 touring model ($10,000) as it struck the right balance between cost and quality, power and utility, and is able to carry two passengers, which my 93-year-old mother enjoys immensely. It also comes with a winch that I keep finding uses for. The 600cc engine is beefy enough to yard logs and tow trailers of firewood or gravel, and the fuel-injected engine always starts and runs well.

Field and brush mower

Throughout our Oakville and Bucoda forests, we have approximately four miles of forest roads and trails that we mow every year. I used to hire a neighbor to mow everything with his tractor, which cost upwards of $1,500 annually. With that recurring cost in mind, shortly after I acquired the ATV, I purchased a DR 44” wide 20 HP tow-behind field and brush mower ($5,000). It takes about eight hours to mow the roads and trails on both of our properties combined. The mower works best on grass if you drive no faster than 3-5 MPH, and since each road requires 3-4 passes to completely mow, this provides a good opportunity for me to observe what’s going on in the woods around me. It’s also very useful for holding the line on blackberries along property lines, mowing between rows of planted trees and shrubs, and tackling other brushy margins of the land. The marketing propaganda that sold me on the machine boasted of its ability to cut woody stems up to 3” thick. However, I find anything this large stops the blades cold, causing the drive belt to jump off the blade pulleys, requiring about a 20-minute repair job.

Chipper

For a reason she’s yet to explain, my mom has always wanted a wood chipper, so about a year ago she offered to sponsor one for the family forest. Chippers typically come in two sizes: too small to be useful or too large to be affordable. However, I found a used Big Bear 15 HP chipper ($3,000) that appeared to split the difference, and we towed it down the freeway to our Oakville land at 45 MPH much to the amusement of all the passersby. The marketing propaganda for this machine boasted of its ability to chip branches and small logs up to 5″. I didn’t believe that for a minute, but was still eager to test out its capabilities. I quickly found that anything much larger than 3” causes the machine to bog down, make horrible noises, and shred the drive belts in a cloud of acrid black smoke. I also found that anything much less than half an inch thick gets stuck between the chipper drum and the housing, causing the drum to seize up, the machine to make horrible noises, and the drive belts to shred in a cloud of acrid black smoke. However, once I found the Goldilocks zone for the chipper, it has turned out to be a remarkably capable machine and produces a chip size that’s perfect for mulch or pathways. My mom also can’t get enough of it, and will contentedly run branches through it until someone forces her to take a break. Big Bear chippers are designed in Utah and have excellent customer service. They also appear to be well built and so far, have been relatively easy to work on.

Chainsaws

Chainsaws are like underwear: when you pack for a trip, you should always bring one more than you think. My general take on chainsaws is to size them for the job at hand. You don’t look cooler cutting a small tree with a large saw, and you’re guaranteed to get tired a lot quicker. There are a lot of opinions about the importance of size, and I don’t want to engage in too much hubris, but I think a sharp chain matters more than size. With a little patience, a small saw with a sharp chain can cut through a larger tree just fine. That being said, here are the four saws I most commonly use:

Husqvarna 550XP 20”

My 550 XP ($650) is my workhorse for tree felling and cutting firewood. Since none of the trees I cut in my woods are more than 20” in diameter, I don’t need a larger saw. This saw strikes a good balance between weight and power, and the auto-tuning carburetor alleviates the need to tinker with the air and gas mix.

Stihl 211 16”

Stihl’s 211 ($340) has plenty of oomph for cutting trees up to 12” – 14”, and is considerably lighter than the 550, which makes it my go-to for pre-commercial thinning and as a back-up for my 550 when felling slightly larger trees. Although a homeowner grade saw with less durable components than Stihl’s Pro grade saws, my 270 has performed marvelously for years with occasional but regular use.

Stihl 170 14”

Although quite small, as compared to the 550, Stihl’s 170 ($220) is still capable of cutting trees up to 10” – 12”. However, I rarely use it for anything of that size, and find it functions best when working in very young stands comprised of dense, small diameter trees. Given its light weight, I can use this saw for a much longer period of time than the previous two. The downside to the short bar is that I have to either lean over or get down on my knees to cut trees or stumps at ground level.

Makita 36V 14”

I’m slowly endeavoring to decarbonize my power tool inventory, and a Makita 36V chainsaw ($380) was the first electric forestry tool I acquired. This is the saw I throw in the backseat of my truck whenever I know I’ll be driving in the woods as it always starts, and is great for clearing small trees and branches off roads. I’ve even felled trees upwards of 12” with it just to see if it could, and sure enough: sharp chain + patience = success. I’ve found that a pair of 18V batteries last almost as long as a tank of gas in a regular saw, sans the nasty fumes and hydrocarbons, making it a compelling option for more and more forestry tasks.

Brush cutters

After a chainsaw, I find a brush cutter is the next most indispensable tool for forest management. Brush cutters have a wide range of attachments, and can be used for trimming grass, scarifying planting sites, or cutting blackberries, heavy brush, and even small trees.

Stihl Kombi

My Stihl Kombi ($400) must be at least 20 years old and still runs with remarkable reliability. It has a strong engine, and with the right blade can cut saplings up to a couple inches in diameter with ease. The detachable end allows for a variety of attachments, although I currently only have a pruning saw attachment (aka chainsaw on a stick) and a grass/brush cutter attachment. The best all-purpose blade, in my experience, is a mulching blade with downturned ends. These make short work of blackberries and most woody vegetation.

Makita 36V

In my ongoing bid to become carbon free with my forestry tools, I recently purchased a Makita 36v brush cutter ($500). The marketing propaganda for this machine said its power is equivalent to a 30cc gas brush cutter, which is almost as big as my Stihl Kombi. I was skeptical, but so far this tool has performed remarkably well and has been able to cut nearly everything a gas brush cutter can. The cutting head can also be run in reverse to clear any vegetation that gets tangled up in it, which gas engines can’t do.

Pruning saws

Pruning trees is one of my most favorite activities in the woods. When using a manual or electric saw, it’s a quiet task that, to my eye, really improves the aesthetic of a forest’s understory. I typically prune the first 12’ – 15’ of branches to both reduce fire risk and improve line of sight through the woods.

Silky pole saw

About 15 years ago NNRG hosted a tree pruning workshop and Silky was gracious enough to donate a telescoping pole saw to us ($500). I’ve been a faithful steward of the tool ever since, and it’s one of the favorites in my inventory. The long Japanese blade is made from high quality steel and has remained remarkably sharp over the years. The large teeth cut aggressively, and with only a few pulls it will cut through branches up to three inches thick. It telescopes out to about 16’ and the oval shape of the shaft helps maintain rigidity when extended. The saw gets heavy quickly when using the entire thing, so I often just pull the first length of shaft out of the telescoping portion of the handle to limb the lower branches of trees up to 12’ – 15’ high.

Stihl Kombi

I have a pruning saw attachment for my Stihl Kombi ($200) which turns the brush cutter into a chainsaw on a stick. In its regular configuration, I can usually reach up to about 10’ – 12’, but multiple 4’ extensions can be added for greater height. I rarely use the pruning attachment, however, as I find that to prune to any meaningful height requires holding the brush cutter’s engine near my own head, thus fumigating me with 2-cycle engine smoke. Hence the next tool…

Electric pole saw

I recently acquired a telescoping 24V electric pole saw ($120) that is showing some promise as an alternative to either the manual pole saw or the Stihl gas version. I opted for an inexpensive off-brand that so far has proven to be quite effective. The powerhead can be detached from the pole and used as a handheld saw, thus increasing its utility. The marketing propaganda for this tool said it could be extended to 16’. However, the round shaft gets pretty floppy at that length, so I typically only extend it out to about 10’ – 12’.

Solar Generator

I use a portable solar generator system to keep the batteries for my electric tools charged when I’m working with them for more than a few hours. A pair of 5ah 18v batteries will run my electric saw or brush cutter continuously for nearly 30-40 minutes, and it takes about this long to recharge the batteries. Therefore, I typically bring two sets of batteries with me so one set is charging while I use the second set. There are numerous options on the market for portable generators and panels, but my current configuration includes a 1200wh generator ($400) paired with a 100w set of panels ($200). If the generator is fully charged to begin with, it can recharge the 18v batteries several times even without being supplemented by the panels, making it an effective option during overcast days.

Hand tools

When I go on my walkabouts, I carry a wide variety of tools with me depending on the task at hand. At a minimum I nearly always carry a folding pruning saw and a machete. I have an insatiable desire to prune the lower branches of nearly every tree I pass, and the machete helps to keep blackberries from infringing upon roads, trails, and newly planted tree seedlings. If I want to take some measurements of my forest, then I will also pack along a small suite of inventory tools.

Folding saw

I’m not brand-loyal with folding saws and I seem to rotate through 1-2 of them every couple of years as they either break or get lost. I’ve had a Stihl folding saw ($42) for a few years now, which is longer than nearly any others I’ve owned. My only word of advice is to spend a little extra to obtain a saw with a high-quality blade that is replaceable, and buy at least one replacement. Cheap saw blades are typically flimsy and bend easily, making it a pain to fold back into the handle.

Machete

Same advice with a machete ($30); spend a little extra to get one with a solid steel blade that won’t bend and can be sharpened time and time again. I recommend tying a piece of orange plastic flagging to the handle to aid in locating the tool when you inevitably set it down in a thick layer of shrubs.

Diameter/Spencer tape

Over the years I’ve become fairly good at estimating tree diameter to the nearest inch. However, a diameter tape is still useful for calibrating my eye or collecting more accurate measurements within plots, as well as measuring the length of logs. Diameter tapes typically come in either 50’ or 100’ lengths, and I find a 50’ tape ($60) is adequate for all my needs (and smaller and lighter than a 100’ tape). Be sure the tape has diameter increments on one side and distance increments on the other.

Increment borer

Although I’ve used an increment borer for decades, I still find a distinct pleasure in pulling a core from a tree and observing the annual growth rings. Since I am actively thinning my forest, periodic measurements of annual incremental growth tell me if the trees are experiencing the rate of release and growth that I want. There are a few different brands of increment borers, and you can purchase them with bits that come in a variety of lengths. They’re expensive, so I recommend purchasing the shortest bit necessary to get to the center of the trees commonly found on your land ($374 for a 12” Haglof borer).

Laser rangefinder

Laser rangefinders are one of God’s gifts to foresters. This one tool has nearly rendered the Spencer tape/clinometer/calculator combo for measuring tree height obsolete, and saved hours of work in the process ($500 and up). Taking a quick height measurement and combining it with the basal area of a stand also yields a quick estimate of timber volume, as I explain below. I frequently also use my rangefinder to count the number of trees within a specific plot size (e.g. 1/20th-acre plot = 26.3’ radius) in order to determine the stocking density of trees (e.g. trees per acre) in my woods as I move from area to area.

Thumb (Basal area gauge)

Although I still carry a basal area (BA) gauge ($16) in my cruiser’s vest, some years ago I discovered that the width of the large knuckle on my left thumb ($0) is equivalent to a 20-factor gauge, and the large knuckle on my index finger ($0) is equivalent to a 10-factor gauge. Thus, in many stands I can literally stick my thumb up and measure the average BA. Most people can only boast about that.

One handy use for BA is estimating timber volume. If you multiply BA by the height of an average tree in your stand and the resulting number by 1.5, you will arrive at the total board feet of timber in a stand (BA x average tree height x 1.5 = MBF).

Planting shovels

Every year I either plant or transplant dozens to hundreds of tree and shrub seedlings. Given the repetitiveness of the task, having the right shovels makes all the difference.

Tree planting spade

I like long-handled, narrow-bladed tree planting spades ($80) for bareroot conifer seedlings. The long handle makes it easier to rock the blade back and forth in the soil to create a good planting wedge. A wooden handled shovel is also relatively light and can be carried all day without undue fatigue.

Long-handled spade

For bareroot hardwoods, I typically use a conventional long-handled spade. I find I can dig a more suitable hole for broad tree roots with a spade than with a narrow-bladed tree planting shovel (although the latter will suffice in a pinch).

Planting bar

The soils at two of the three woodland properties my family owns are comprised of silty clay loam, which makes tree planting about as easy as planting into chocolate cake during the winter. Our third forest is underlaid with glacial till, which makes tree planting a bit more challenging. For this site, I prefer a planting bar ($72) made of heavy steel as it’s much more suitable for prying into rocky soil to create a planting hole.

Phone

Aside from taking photos, recording notes, and posting images to my Keeping Up with the Hanson’s Instagram account, I also use my phone for mapping and documenting observations.

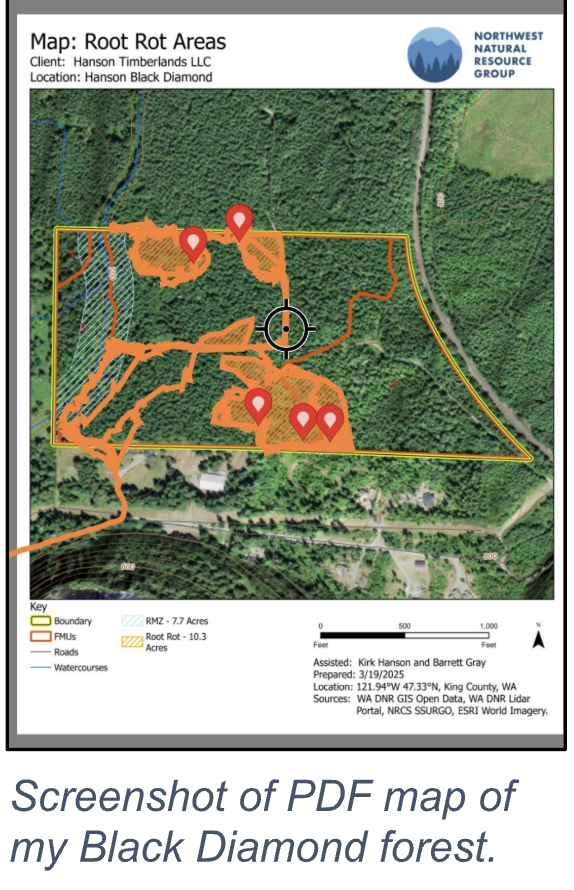

Avenza app

Avenza ($0 for basic functions) is a very useful mapping app that uses georeferenced PDF maps. A user can record a track they walk through the woods and put in placemarks to which can be attached photos and/or notes. I find this app quite handy for regular forest monitoring. For a small fee, NNRG’s cartography staff can produce a highly informative resource maps for woodland properties that include the following data: soils, topography, hydrology, tree heights, and more.

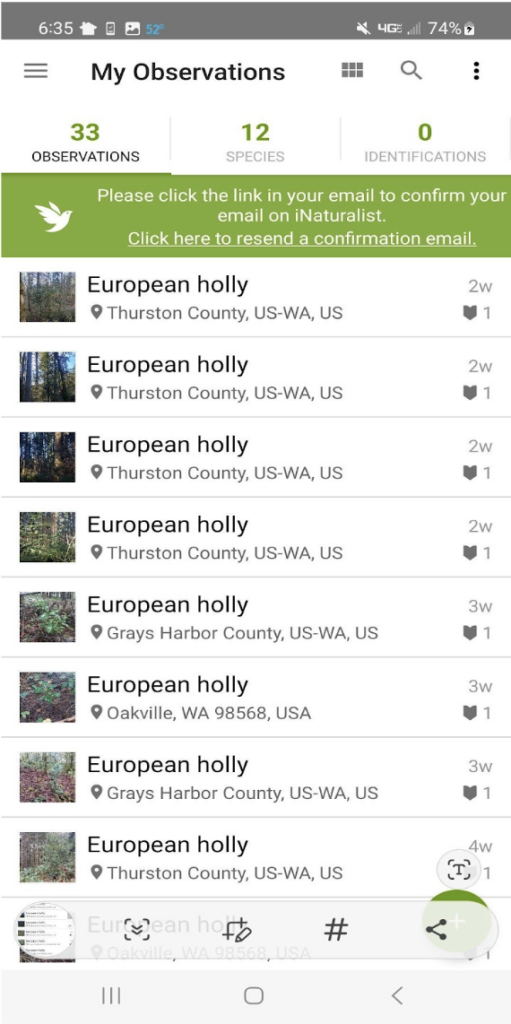

iNaturalist app

iNaturalist ($0) is a really interesting app that allows users to post observations of natural phenomenon, particularly wildlife species and plants. Researchers are increasingly turning to iNaturalist to document the spread of invasive species and the migratory habits of birds, amongst other useful data. So far, I’ve only been posting occurrences of nonnative plants and forest health issues such as western redcedar and maple mortality.

Clothes

Albeit not a tool, the right clothing makes all the difference when tinkering day after day in the woods.

Gloves

I’m a fan of leather gloves ($20) (at least leather palms) as they’re far more effective at resisting blackberry prickles than most other material, and leather has a grippiness whether it’s wet or dry.

Boots

Three boot styles make up my footwear. I have a pair of heavy leather calks for chainsaw work during the summer months and rubber calk boots for winter work. Both are manufactured in the US by Hoffman Boots ($330 and $165 respectively). For general meandering around in the woods I like barefoot boots. The soles of barefoot boots are designed to protect your feet while providing optimal traction and sense of connection to the ground. They also feel like an ongoing reflexology session, as every area of the foot’s sole is “massaged” by the texture of the ground. There are numerous manufacturers and styles, but my current favorite is Vivo Barefoot’s Tracker-Forest ($280)

Brush pants

We have A LOT of blackberry in all three of our family’s forests, and wading through it is an inevitability. Although double-front logger’s dungarees are certainly durable and can fend off blackberry thorns tolerably well, I find they get heavy quickly during a hot and sweaty day and don’t always provide the greatest range of movement. For an alternative, I’ve become a fan of brush pants ($40 – $100) that are specifically made for, well, walking through dense and prickly brush. They have reinforced fronts, often made of ripstop fabric, that I find is superior to turning aside the sharp advances of blackberries. They also tend to be roomier and more breathable. I’ve tried several brands, and haven’t settled on a favorite yet.

Are you interested in learning more about the tools of the trade? Join us for our February 18 fireside chat where I’ll lead a discussion on the tools I rely on in the woods, and invite others to share their favorites. If you’re not able to join us, you can find recordings of past fireside chats here.

One Comment

Very helpful commentary on tools, Kirk. I’m surprised that you didn’t include a peavey for moving logs around. Is such a tool too old-school now?