Monitoring Mount Heaven

Last spring, Paul Hansen and his 16-year-old granddaughter found themselves tromping through his forest near Mount Rainier (Tahoma), in Washington.

Both were searching for old PVC pipe remnants and rebar stakes hammered into the ground, but their motives that day were split. Paul was hoping to find the centers of circular plots he’d marked out 10 years prior in order to do regular inventory of his young forest near Eatonville, Washington. His granddaughter was hoping to spend some time with granddad…and take home the promised $50 bribe in exchange for the inventory assistance.

While GPS coordinates helped guide them to the rough location of the markers, it took a bit of additional sleuthing through the understory to find the old markers themselves; evidently at some point an elk or two had mistaken a few of the PVC pipes for trees they could rub against, and broken them to pieces.

Paul Hansen’s forest is called Himmelbjerget. He and his wife Judith bought the land in 2004, and named it in honor of Paul’s Danish father. “Himmelbjerget” is the name of the highest peak in Denmark, a hill about 600′ above sea level (Denmark is not a mountainous country). In Danish, “Himmelbjerget” translates to “Mount Heaven” or “Sky mountain”.

“I chose it because of our proximity and fantastic view of Mt Rainier, which is our version of mount heaven,” says Paul. “Also, the highest point on our property is about 600′.”

At the time, much of the property had been recently clearcut and replanted, and the Hansens set to work replanting trees in other recently cut areas.

Over the years, Paul and Judith attended various NNRG workshops and university forestry extension events, and heard repeatedly about the benefits of setting up permanent monitoring plots and conducting timber inventories. “It seemed like most of the professionals were doing it,” says Paul. “And we had the perfect opportunity.” With most of their trees so young, the Hansens would be able to monitor their trees from seedling to snag (or log, if they decided to harvest in the future).

Conducting a Timber Inventory Using Permanent Monitoring Plots

Permanent monitoring plots provide a system of tracking changes in a forest over time. By collecting stand data like average tree diameter, tree and understory species composition, stand density, and average tree age every 5-10 years, a forest manager can note changes in their forest and make better informed management decisions.

Paul decided to establish permanent monitoring plots at Himmelbjerget in 2012. The 24-acre property has four distinct stand types, and in each Paul selected between four and six randomly-distributed plot centers and used rebar hammered into the ground and painted PVC pipes to mark their locations. He also recorded the GPS coordinates of every plot center.

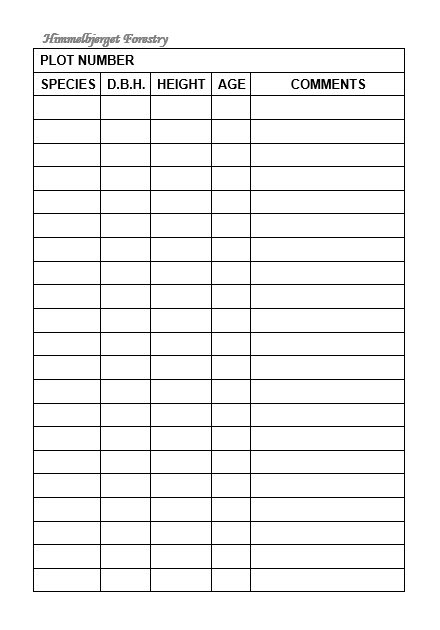

Then, measuring a radius of 26.3’’ from each plot center, he recorded the species, DBH (diameter at breast height), and age of every tree within the stand. He also noted whether the tree had any defect or other unusual attribute. Most of the trees were between 3 and 6 six years old at the time, and were barely peeking out over the understory shrub layer.

Then, he let the trees grow. “My plan was to do the inventory every five years,” says Paul. But, life got in the way, and the next opportunity for an inventory came 10 years after the first.

This time, Paul had his granddaughter to help him collect the data. Being a teenager, the help was granted in exchange for $50. And, “she stole my steel hardhat and wore it the whole time,” says Paul.

Paul hasn’t transferred the inventory data from either survey from paper to digital format yet, but he plans to record all the data in an Excel spreadsheet eventually. As his forest grows, he’ll be able to refer to the inventory data to make forest management decisions – for example, when to pre-commercially thin a stand or underplant a stand with additional species. If the incremental diameter growth of trees in a particular stand begins to decrease, that may indicate the stand has entered a competitive growth phase and trees are favoring height growth over diameter growth. This can result in a forest that’s both ecologically and economically undesirable – densely packed with tall, spindly trees with diminished crowns and thin stems that aren’t commercially viable and don’t offer adequate habitat for a diverse wildlife population.

The Himmelbjerget Log of Recordable Events

The timber inventory isn’t the only monitoring Paul is doing at Himmelbjerget. He also keeps a “log of recordable events” – essentially, any notable things Paul sees, hears, or experiences in the forest. Wildlife sightings, in-person and captured by wildlife cameras, make up most of the log entries, but management activities like cutting brush or spraying invasive species with herbicide also make the cut.

“One time, I had a great horned owl scare the life out of me,” Paul recounts. “My wife and I were walking along a trail that loops through the property, and this thing came up from behind me and brushed the top of my head and then flew on in front of us. It was totally silent but I felt the breeze as it flew over me. It had huge wings that seemed like they were 20 feet long.”

Coyote, cougar, elk, and deer show up on the wildlife cameras placed throughout the forest pretty frequently. Last summer the forest was visited by a family of black bear with a young cub. Once, a long-tailed weasel showed up on one of the wildlife cameras, and hasn’t been spotted since.

Paul and Judith get a lot of joy out of the wildlife in their woods; a few years ago they even received EQIP funding to install small bird and waterfowl nesting boxes throughout the property, in addition to doing scotch broom removal after a replanting project. They plan to continue recording notable events and all wildlife sightings in the log in perpetuity, a task made easier by the recent move to living in a house on the property full-time. “We moved in in late 2019,” says Paul. “Just in time for covid to hit. We were fortunate, while everything was so locked down, to be able to go for walks in our woods.”

Learn more about forest monitoring and find inventory tools here. NNRG’s guidebook on conducting a forest inventory is available here.

Leave a Reply