Living with Wildfire

Fire has shaped the forests of the Pacific Northwest since time immemorial — and it’s here to stay. But decades of fire suppression, the prohibition of Indigenous burning practices, and a hotter, drier climate have made wildfires more severe and unpredictable. For landowners and communities across the region — especially those living in the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) — understanding local fire risk and taking proactive steps to reduce it are more important than ever.

Understanding Fire Risk

Forests across the Pacific Northwest vary in fire regimes and management needs — as OSU’s extension service puts it, “not all flame’s the same.” West of the Cascades, recent data from fire scars on tree rings suggest that smaller, sub-catastrophic fires were more common than previously thought, but severe wildfires are historically infrequent — burning only once every 100-400 years. When conditions align, these fires can burn at such high severity that most trees are killed, resetting forest succession.

The region’s high biological productivity means large amounts of biomass accumulate each year, creating vast stores of burnable fuel that usually stay damp due to the Northwest’s high rainfall. During dry summer months, however, these fuels become increasingly flammable. While many ignitions (from lightning or human activity) remain small surface fires, extreme weather with hot, dry air and high winds can quickly turn a small blaze into a crown fire that spreads across thousands of acres.

Local fire risk is shaped by ignition sources, fuel loads, and accessibility for firefighters. Roads, public access, and development all increase the chance of human-caused ignitions. Stands with dense young trees, low canopies, and abundant shrubs or downed debris are more likely to allow a surface fire to climb into the canopy.

Reducing Fire Risk in Forests

It’s important to know what fire regime — the common pattern of fire intensity and frequency — pertains to your forest. A lot of the press about wildfire preparation refers to strategies like thinning dense stands and pruning lower branches, which are effective in dry forests at lowering fire severity and improving resilience to drought and insects. That works well in a high-frequency, low-severity fire regime.

But in wetter forests, like the ones found west of the Cascades, the fire regime is one of higher severity and lower frequency, and management options are more limited. While management practices, like thinning to reduce stand density, are important for maintaining a healthy forest, they may not significantly lower the risk of severe wildfire. The infrequent but severe fires that these ecosystems have historically experienced typically occur under extreme conditions. As a result, thinning and fuel treatments might not significantly change fire behavior because large fires in these systems often burn during severe drought and high wind.

While our ability to reduce wildfire risk in these wetter forests is limited, there are still some management strategies that can help lower risk and improve overall forest resilience. These strategies include:

- Prioritizing and protecting important resources, like municipal watersheds, critical wildlife habitat, or valuable infrastructure with fuel breaks to reduce fire intensity and facilitate fire suppression.

- Promoting landscape heterogeneity, as healthy forests with diverse species mixes and stand structures are more resilient to wildfire.

Other practices for reducing the risk of wildfire, particularly in drier forests, include:

- Thinning: Remove small, suppressed trees to increase space between crowns and reduce ladder fuels. This encourages larger, more vigorous trees that are more resistant to fire.

- Managing fuels: Minimize fine branches and slash on the forest floor, and avoid slash piles that exceed 24 inches thick.

- Pruning: Remove lower branches up to 15 feet (or three times the height of the dominant shrub layer) to prevent ground fires from reaching the canopy.

- Maintain road access: Keep forest roads open and passable for emergency vehicles.

- Mix in hardwoods: Maintaining at least 10–20% hardwoods in your stand helps reduce overall fire risk and speeds forest recovery after a fire.

It is also important to minimize the risk of starting a fire while working in your forest:

- Watch where you park your car. The undersides of cars, particularly catalytic converters, can get very hot. The exhaust pipe is another problem area. Whenever possible, try not to park your car over dry grass, brush, or leaf litter. Stick to gravel, dirt, or rocks.

- Check your car for low parts that could spark. Low-hanging mufflers or chains that drag or bump the ground are liable to spark. If you’re towing a vehicle behind your car, make sure any tow-chains are fastened tightly enough so that they don’t drag.

- Check and regularly maintain your tires. Once a flat tire shreds, the bare wheel can shower sparks on roadside vegetation.

- Keep a wildfire kit in your car. This might include a shovel, work gloves, protective goggles, and a fire extinguisher.

Reducing Fire Risk Around Structures

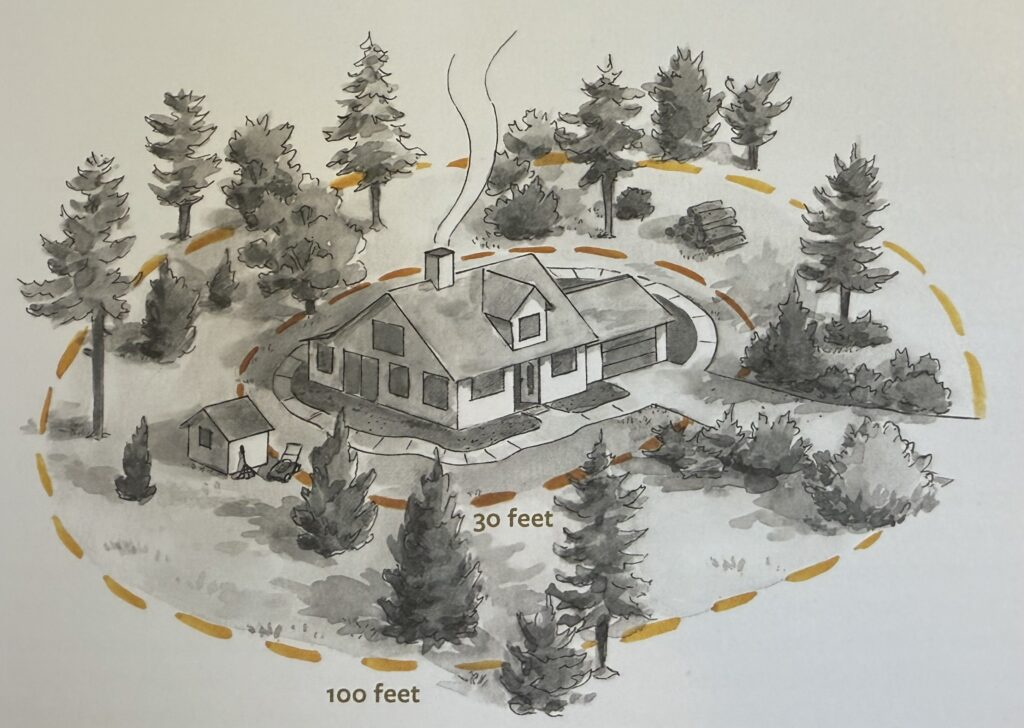

Whether you live in a home on your forestland or just have a structure or two, there are steps you can take to protect the buildings on your property from wildfire. The first 100 to 200 feet surrounding any structure should be actively managed to slow or stop fire spread. Note that county permits are often required for tree cutting in these areas.

- Zone 0 (0–5 feet): Keep this area clear of any flammable materials, including vegetation, mulch, and wooden structures.

- Zone 1 (5–30 feet): Keep this area lean, clean, and green. Space vegetation well apart, prune tree limbs to 6–10 feet from the ground, and remove ladder fuels like shrubs under trees. Avoid storing firewood or flammable materials next to buildings.

- Zone 2 (30–100 feet): Thin trees to maintain at least 10 feet of spacing between crowns. Remove small diameter trees and dead vegetation, and prune branches up to 10–15 feet to keep fires from climbing into the canopy.

- Zone 3 (100–200 feet): Thin trees selectively to maintain healthy tree and understory growth.

For more information on protecting your home and other structures, see the WA DNR’s 12 Steps to Defend Your Home from Wildfire for a detailed checklist, the U.S. Fire Administration Healthy Landscapes guide, or the National Fire Prevention Association’s guide to preparing homes for wildfire.

Stay Safe as a Community

Your efforts are even more effective when neighbors work together to stay prepared and informed. One option is developing a Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP). CWPPs are collaboratively developed plans that help communities reduce their wildfire risk and prepare for fire. In addition to helping communities prepare for fire, those who have CWPPs are given priority for USFS and BLM-funded hazardous fuels reduction projects under the Healthy Forest Restoration Act of 2003 (HFRA). Many communities across Oregon and Washington have already established CWPPs — to see if your community has one, check the state websites for Washington and Oregon.

Some other helpful tools include:

- The USDA Wildfire Risk to Communities website has interactive maps, charts, and resources to help communities understand, explore, and reduce wildfire risk.

- WDNR Burn Risk Map

- Oregon Wildfire Risk Explorer

- OSU Extension Wildfire Readiness

- Wildfire Outreach Toolkit, which includes the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) Fire Property Awareness Explorer and the WUI Fire Community Awareness Explorer

Many counties and conservation districts offer resources to help landowners and communities reduce the risk of wildfire. For example, Skagit and Whatcom Conservation Districts provide free programs that help residents understand their property’s wildfire risk and take steps to protect their homes and forests.

Financial Assistance

Many landowners can access cost-share funding and technical help for wildfire mitigation projects like vegetation removal, hardscaping, gutter and roof maintenance, fuel breaks, and forest stand improvement. For more information about these programs, please visit NNRG’s Funding Fuel Reduction and Forest Health Projects list.

Wildfire is a natural part of Northwest forests — and with thoughtful stewardship, you can reduce risks to your home, your woods, and your community. Whether you’re managing a dense stand, protecting a home, or planning with neighbors, taking proactive steps now can help your forest thrive in a changing climate.

Leave a Reply