Making a Good Co-Home

There’s a hint of expectation in the air around Lousignont Creek, located in the northern Oregon Coast Range.

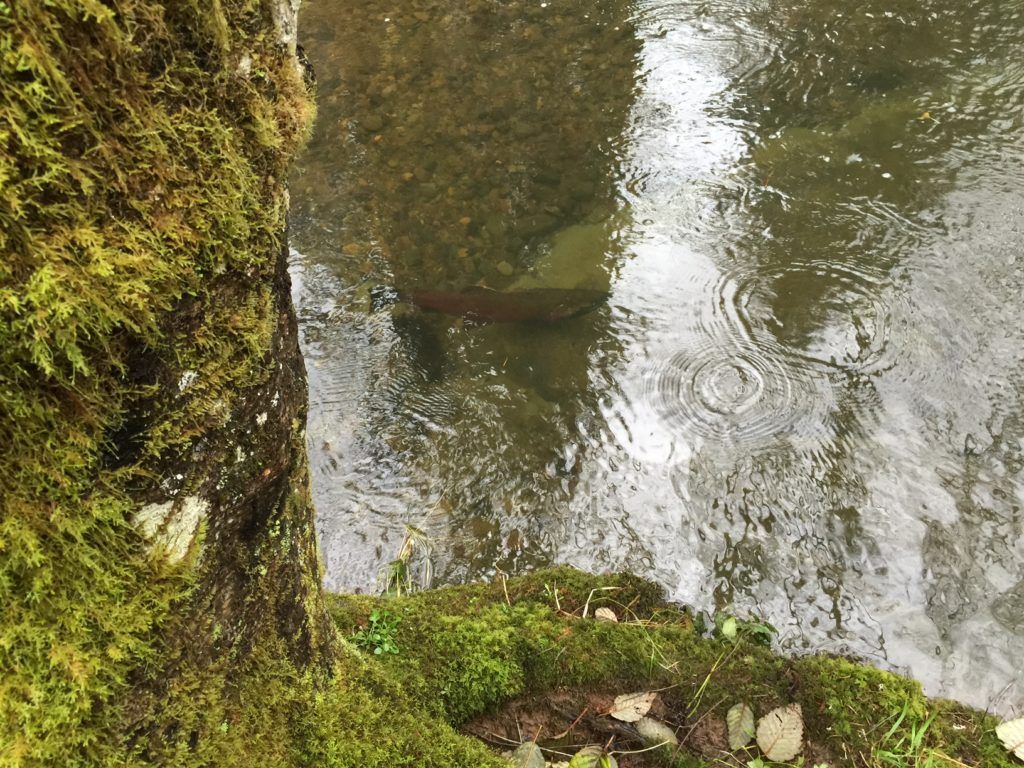

Sometime in the next two months, adult coho salmon will appear as if out of nowhere and struggle upstream in search of suitable gravel for spawning. There, each female coho will lay a nest of eggs, called a redd, and a male coho will hopefully come along to fertilize it. The same adults were born in Lousignont Creek just 2-3 years ago. Since then they’ve traveled thousands of miles to the coast, around the Pacific Ocean, and back to Lousignont Creek.

It’s a coho homecoming. A cohomecoming.

Lousignont Creek flows through one of three working forests owned and managed by Pam and Peter Hayes. Together these forests make up Hyla Woods, which is a member of NNRG’s group FSC® certificate and a family-owned business that uses ecological forestry techniques to grow ecologically complex, economically viable, responsibly operated forests. Pam and Peter do some of their logging and milling in-house, in addition to hiring logging contractors and selling logs to other mills. They’ve built a solar-powered kiln to dry their own wood.

The Hayes family and their partners have front row seats to the coho’s annual return, but their attitude has been more akin to that of an Olympic organizing committee than a stadium of spectators. In partnership with various stewardship organizations, they’ve spent more than three decades restoring Lousignont Creek—making it more hospitable for coho, which are endangered, and other aquatic species.

According to Peter, prior to the restoration work Lousignont Creek lacked good character. And before you ask—he’s not talking about what the stream does when it thinks no one is looking.

He’s talking about variation in the stream’s banks and beds. Complexity in its structure.

Up until 1980, woody debris was often removed from rivers and streams due to the misconception that it posed a barrier to migrating fish. In fact, the opposite is true: big woody debris creates essential juvenile salmon habitat by creating pools and eddies providing essential habitat for insects that make delicious fish food.

Unencumbered by wood, a stream will flow faster than usual, in time eroding stream banks and depositing sediment into the water. Too much fine sediment in the water can adversely impact salmon by restricting oxygen flow to their eggs.

In partnership with the Upper Nehalem Watershed Council, and along with their upstream and downstream neighbors, the Hayes have been installing wood placements in Lousignont Creek for 30 years. Logs from their forest, including some with root wads still attached, are strategically placed in the creek to form large log-jam structures. These, in turn, begin to ‘recruit’ their own wood as they trap logs and branches flowing downstream.

Noxious weed removal has been a second important component of creek restoration. Historically, parts of Lousignont Creek were beset with reed canarygrass, an aggressive perennial that readily produces a dense mat of shoots in freshwater ecosystems. Aside from shading out native plants, reed canarygrass also channelizes the stream and traps sediment—which, again, creates that low-oxygen environment that’s bad news for fish.

Combatting reed canarygrass is an enormous challenge, which the Hayes have dealt with head-on. “We regraded the whole area,” says Peter, referring to the section of the creek clogged with the weed. In place, they’ve installed more big woody debris and native plant communities.

This restoration work is only the beginning of the solution. “We’re just priming the pump on helping the system become regenerative on its own,” says Peter.

“We work with the philosophy that intentions are nice, and actions are good, but outcomes are what really matter.” The Hayes have a monitoring program in place for the stretch of the creek they worked on since 1986, which will help them track the outcomes they’re hoping to achieve. Results show that ecological restoration is succeeding.

When we spoke to Peter recently, he made an important point that’s easy to forget: riparian health is about more than just managing the area around the water. “A lot of restoration is focused on the riparian corridor,” says Peter. But the health of the water is dependent on more than just the 50-foot buffer on either side of it. “If we want healthy streams, we need healthy uplands. Our riparian work is not isolated from what we’re doing in the rest of the forest.”

And with that, Peter has hit the nail on the head of ecological forestry.

It’s a philosophy that treats the forest as more than just the sum of its parts. To ensure a healthy stream you must ensure a healthy forest. It’s clear that this is exactly what the Hayes are aiming to do in Hyla Woods.

This month when the coho make their way back up the Nehalem River they’ll find refuge in Lousignont Creek, where every year the water is a little clearer, the flow a little slower, and the dinner menu a bit more expansive. And Pam and Peter will have made a little more progress toward their goal of growing ecologically complex, economically viable, responsibly operated forests.

Interested in learning more about stream, salmon, and trees? Join the Build Local Alliance and Hyla Woods on December 14th for an educational hike exploring the interdependent relationship between salmon and forests. Register here.

Hear from the Hayes in their own words about the coho’s return to Lousignont Creek on the Hyla Woods blog.

Leave a Reply