Moving Trees: Definitions and Ethics of Assisted Migration

In every discussion of forest restoration or climate adaptation, someone asks the question: What about the assisted migration of trees? Should we be doing it? What are the potential impacts? It’s a big topic, and one nuanced enough that it could easily fill a hundred discussions, a dozen doctoral theses, and several books. Our recent presentation and discussion with our partners in the Treeline project, the regional forest adaptation network supported by Climate Resilience Fund was focused on these issues. The event covered definitions and ethical concerns around assisted migration with the aim of gaining some collective clarity on the topic.

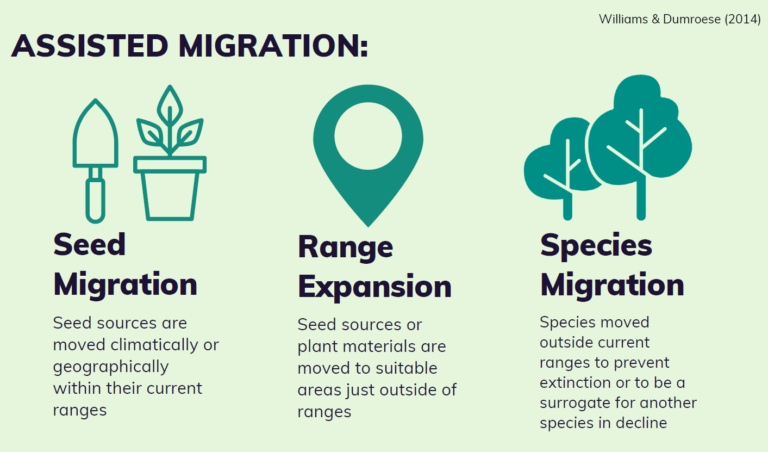

There are several types of assisted migration. A simplified framework used in our recent discussion differentiated between the movement of seeds within their range, the movement of seeds and plants to just outside their current range, and the movement of species outside their range. (There are more detailed definitions in a paper by Dumroese et al.)

Few practitioners have concerns about sourcing seeds from drier and warmer areas in the same seed zone, but there are concerns about sourcing new species from a different seed zone (bringing incense cedar north of its current range, for example). Concerns about assisted migration range from the potential for introducing pathogens to concerns around erasing species that have been part of a region’s ecology and cultural practices for thousands of years.

In addition to the risks of assisted migration, however, there is a sense that the risks of inaction are greater. While some are reluctant to intentionally change the ‘natural order of things’ by changing a species’ range, most recognize that many of the systems we work within are already fundamentally altered from their ‘natural baseline’ state.

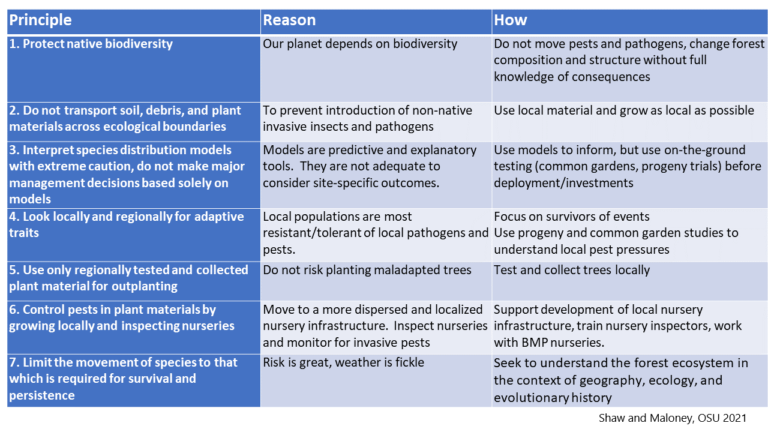

There are few legal regulations and little guidance around assisted migration, and generally little appetite for increased oversight. Thus, it generally falls to practitioners to develop standards of practice. One approach recently proposed and being refined by Shaw and Maloney (Oregon State University) outlines seven principles to encourage cautious and thoughtful action by professionals who may be working in this space.

One of the difficulties of grappling with assisted migration is the long-term nature of the impacts and consequences. At the same time, many are motivated to move forward and take action, based on the idea that we have a collective responsibility to address some of the issues we’ve collectively helped to create.

While there’s a tendency to want to wait until we have full information, the reality is that we’re already working in a changed system, which will continue to change. However, science is iterative rather than absolute, and the actions we take to restore ecosystems and address climate change will need to be iterative as well – and, we hope, well-documented. It’s the definition of adaptive management.

In order to mitigate risk (and because of practical time and funding restrictions) many practitioners are advocating for ‘baby steps’ in the migration process. And at the end of the day, we are working with natural processes that have been honed over countless years, so the best bet is following the lead of the true ecosystem expert: Nature itself.

Leave a Reply