Riparian Restoration Along the Skookumchuck River

Often when landowners come to NNRG for forest restoration help, our aim is to turn a dense, uniform forest that is susceptible to pests, disease, and fire into a more heterogeneous, resilient forest that supports a diversity of wildlife habitat and (sometimes) provides long-term timber revenue.

In 2021, NNRG was hired to spearhead an entirely different sort of forest restoration in the Skookumchuck Wildlife Habitat Management Area northeast of Centralia, Washington. This unique and ongoing project entails restoring native forest cover to former farm fields along the banks of the Skookumchuck River.

The Skookumchuck Wildlife Habitat Management Area

In 1970, the construction of the Skookumchuck Dam just east of Centralia, Washington, inundated the dry land on either side of the river upsteam from the dam, creating the 500-acre Skookumchuck Reservoir. The reservoir supplies water to the Centralia Coal Plant, which today is operated by the TransAlta Corporation. Per a 2011 agreement, the Centralia Coal Plant is scheduled to shut down in 2025, but the fate of the Skookumchuck Dam and reservoir remains uncertain.

To compensate for the loss of elk habitat flooded by the reservoir, in 1979 the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and the then-owners of the Centralia Plant signed an agreement to establish the Skookumchuck Wildlife Habitat Management Area (SWHMA), a 960-acre property downstream of the dam that would be managed for recreation and wildlife habitat, with a focus on elk habitat and forage areas. The SWHMA contains a huge variety of natural areas, including grassland, wetland, former farmland, meadow, orchard, and forestland. In addition to elk foraging grounds, the SWHMA protects important habitat for winter steelhead, fall Chinook, coho, Pacific lamprey, and cutthroat trout.

Returning conifers, shade, and large woody debris to the Skookumchuk River

Fast-forward four decades, and the SWHMA is still designated for wildlife and recreation. However, little has changed along the banks of the Skookumchuck river, and the habitat and riparian functions remain in a degraded condition, much as they were when the area was farmed over forty years ago.

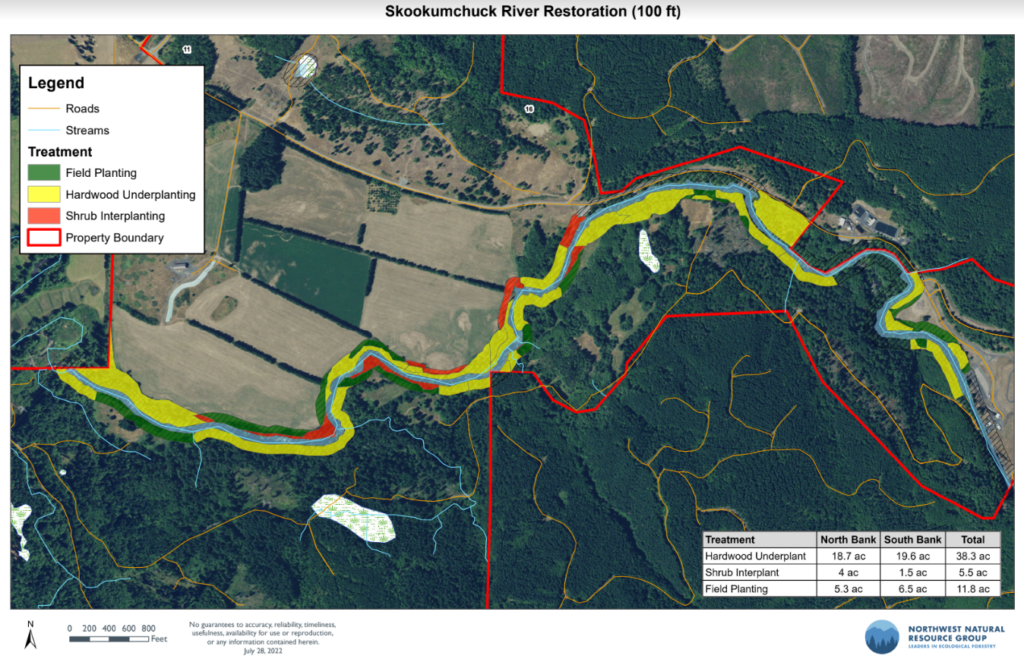

Thus, in 2021 a plan was launched to restore native forest cover to non-forested and under-forested areas within 100 feet of the Skookumchuck River within the SWHMA.

NNRG’s Director of Forestry Kirk Hanson developed the project plan in consultation with Cafferata Consulting and the Thurston Conservation District. They identified four initial areas of concern:

- Former agricultural fields that run right up to the edge of the river offer few ecological benefits, as no trees or vegetation provide shade, input of nutrients into the water, or stability to steep and eroding banks.

- Other sections of the river are sparsely forested and dominated by red alder and bigleaf maple, many of which are of an advanced age and are falling apart.

- Still other areas are shrub dominated, with a mix of native vegetation and himalayan blackberry, the latter of which frequently occurs in dense, dominant patches.

- A lack of large woody debris in the river reduces channel complexity, leading to an incising of the channel and minimal pools, riffles, or gravel bars that salmonids need for rearing.

Restoring conifer-dominated forest types along both sides of the river in the SWHMA would improve ecological functions important to river habitat, including providing shade, sediment filtration, bank stabilization, and the input of nutrients and large woody debris.

The restoration plan Kirk and the team designed comprised of three main restoration activities:

- Field planting: Planting a mix of native hardwood and conifer trees in former agricultural fields along the river

- Hardwood underplanting: Planting shade-tolerant conifers in sparsely forested areas currently dominated by hardwoods

- Shrub interplanting: Controlling invasive plant species and planting existing shrub-dominated hedgerows with mixed native hardwood and conifer trees.

The map below shows the distribution of these three restoration activities along the Skookumchuck River in the SWHMA.

A challenging project

Restoring grassy fields to forest is challenging, for a number of reasons. Grass dominated areas are some of the most difficult sites to establish trees due to competition from the grass for soil moisture and sunlight. In addition, the tall grasses provide cover to mice and voles, that can girdle seedlings and saplings. Grass, in particular, is extremely water-greedy, and its roots compete for soil moisture in the same soil horizon as the roots of newly planted tree seedlings. Grasses also exude a growth-inhibiting compound from their roots, referred to as an allelopathic chemical, that reduces the vigor of other plants growing in their proximity. Highly aggressive, non-native shrubs that occur along field margins, like himalayan blackberry, can grow over tree seedlings and shade them out quickly. And young, sweet tree seedlings are a delectable treat for elk and deer, which are abundant in the area and will happily munch them down to the ground.

The restoration plan Kirk designed has several means of addressing these challenges.

The plan calls for replanting native trees at a high density, which will help achieve canopy closure (when the crowns of the trees reach each other and shade out the ground below) at an earlier age, thereby accelerating suppression of the grass, as well as other non-native vegetation. Once the canopy of the planted trees closes, the dense new forest will be gradually thinned to reduce competition and allow opportunities for native shrubs and groundcovers to colonize the understory.

In some areas, patches of dense red alder will need to be thinned to provide optimal conditions for the underplanting of shade-tolerant conifers.

Prior to planting seedlings, the planting sites are mowed and sprayed with herbicide to kill off the field grass. Seedlings are planted in rows that are just wide enough to mow through, and paper mulch mats are placed around each seedling to further inhibit grass competition. Competing vegetation is cut back from the seedlings every year, until they are fully established. Most of the seedlings are also protected by tree cages that prevent (or at least slow) deer and elk browse.

As of July 2023, all of the planting sites have been prepped, planted, and are now being routinely monitored by NNRG’s forest restoration team. Every year, crews will return to the planting sites to cut competing vegetation back from the seedlings and check for growth and survival, until the seedlings are tall and robust enough to stand their own against neighboring shrubs and trees.

The funds for this project come from a timber harvest NNRG conducted in a dense forest in another part of the SWHMA. Yet another habitat restoration project, the timber harvest was designed as a variable density thinning that opened the forest canopy to stimulate understory shrub development for deer and elk forage.The harvest netted around $175,000, almost all of which was devoted to this riparian restoration project.

For now, the replanted sites look more like a plastic tube farm than a forest. It will take some time before this area begins to look more natural. But the changes to come will improve the ecological value of the SWHMA and create better wildlife habitat in and along the Skookumchuck River.

Interested in embarking on a restoration project in your forest? Learn how NNRG can help.

Leave a Reply