Some Benefits of Small Clearings in a Sustainable Forest

This article was written by Tim Schomberg, prior of North Cascades Buddhist Priory, which is a member of NNRG’s Group FSC Certificate.

By Tim Schomberg

I manage over 200 acres of forest owned by our church. This forest was once part of a Weyerhaeuser Corporation tree farm of about 900 acres. The whole of the 900 acres had been clear-cut in 1973 and, shortly thereafter, replanted with Douglas fir. Then, in 1986, Weyerhaeuser began selling off parcels segregated out of the tree farm. That is when we purchased our first 20 acres. Right away we started building our church.

Since that time, we have been able to acquire more of the former Weyerhaeuser property in the neighborhood. Our purpose has been to preserve and protect the forest, wetlands, and wildlife.

We wanted to transform our forest from a short rotation, clear-cut, Douglas-fir plantation to a varied forest that would more closely resemble the native forests of the Pacific Northwest. By “varied forest” I mean a forest that has a greater variety of types of trees and shrubs, and also a forest in which the density of trees and shrubs varies.

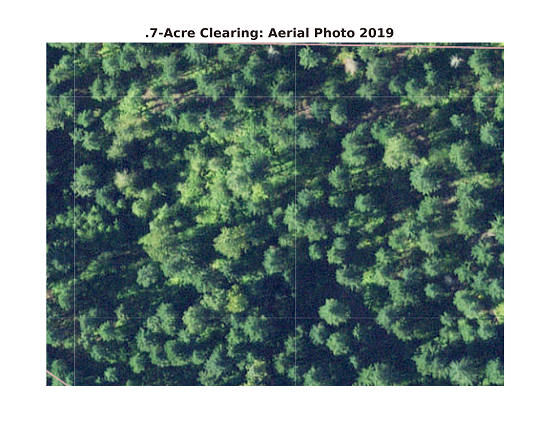

In planning our first major tree-thinning project (2006), I decided to include the creation of a very small clearing. (For the purpose of this series of articles, “small clearing” means “a mini-clear-cut from ¼ acre to 2 acres in size.”) In our second thinning project (2007), we created another, larger clearing. Both clearings were partially replanted by hand with a variety of native trees—none of which were Douglas fir. Also, in both clearings, native shrubs and small trees have been allowed to grow up along with the trees planted by hand.

How Nature Makes Clearings in Northwest Forests

When I think of natural clearings in forests, one image always pops into my mind—the memory of a place in the Wallowa mountains of northeast Oregon where an avalanche swept down a steep mountainside several decades ago. Most of the trees in the path of this great, plunging bulldozer of snow were knocked down, and the ground was exposed to light. When I first hiked through this area almost 20 years ago, a few living trees, and the stark remnants of some dead trees, were still standing in the clearing made by the avalanche. But the most notable feature was a rich growth of shrubs and small trees.

Avalanches tend to create clearings much larger than an acre or two. The same is true of forest fires. Then there are volcanic eruptions, which can clear vast numbers of trees with winds of hundreds of miles per hour, and also with fire, deep ash fall, and lahars (violent mud- and debris-flows that sometimes result from volcanic activity). Heavy rains can result in flooding rivers that can carry away trees along river banks and in river floodplains. Landslides, occasional hurricane-strength winds that sweep through our region, and large-scale disease and insect damage can also create larger-scale forest clearings.

Diseases such as laminated root rot, a fungal disease that affects most conifers in the Northwest, can create small clearings in the forest. The fungus is spread by direct root contact between an infected tree and a non-infected tree. So in a stand of trees such as Douglas firs, an infected tree will eventually be surrounded by a circle of other trees that it has infected. While some trees can live for many years after being infected, they are gradually weakened by the fungus and become more susceptible to being blown down by strong winds. So, over time, laminated root rot can cause small clearings or partial-clearings to open up in the forest.

Even the healthiest tree eventually ages and dies. In an old-growth forest in the Pacific Northwest, when one of the great conifers falls—or when, as often happens, two or three great trees growing in a close clump all go down together—a very small clearing is created. At the foot of the fallen giant will often be found tiny trees (especially Western hemlock) that may look like very young trees, but which may have lived in the shade for decades in a state of arrested growth as they awaited the opportunity to take the place of one of the mature trees. When sunlight at last penetrates through the canopy, the waiting little trees put on a rapid spurt of growth as they race to fill the vacancy. The death of a giant tree becomes the opportunity for renewed life for these trees.

Whether a clearing in a forest is large or small, the net result of its creation is the same: new opportunities for both plants and animals.

The Reasons For Making Clearings

We make small clearings in our forest in order to mimic the naturally-occurring clearings that open up from time to time in Northwest forests. We hope to obtain for our forest the same benefits that these clearings provide to the natural forests.

Of course, tree-thinning, which allows more sunlight to penetrate the forest canopy, also creates opportunities for both plants and animals. For example, within a few years of beginning tree thinning, we noticed an increase in the numbers and varieties of birds on our property. This coincided with a great increase in the number of shrubs such as red currant (very attractive to hummingbirds), salal, and Indian plum (“osoberry”), and small trees such as chokecherry and hazel. All of these plants provide food for birds, and some provide good nesting places as well.

But if tree-thinning, which increases the amount of sunlight that can penetrate the canopy, provides opportunities, creating small clearings, which greatly increases the amount of sunlight, provides even more opportunities. Shrubs and small trees that can endure full sunlight thrive in the small clearings. This creates denser cover and more food for birds and small mammals, and more browse for deer and elk.

Some of the trees that we have planted in our small clearings are members of non-Douglas fir, marketable species that require more sunlight than the thinned forest can provide. Most of these trees are thriving in the small clearings. As will be seen in a future article in this series, there may be good long-term reasons for diversifying the varieties of marketable species on our property.

7 Comments

It’s insightful to learn about tree-thinning and how it can benefit the forest by letting more light be absorbed by shorter plant life. I would understand how these processes are relevant to preserve forest health. So, I think if you are a landowner, hiring forestry management services would really be beneficial if your goal is for overall vegetation health.

This is a great article! Small clearings in forests are such an effective way to promote biodiversity and support sustainable forestry practices. They create spaces for new growth, wildlife habitats, and improved forest health. In the land clearing industry, incorporating sustainable methods like selective clearing and forestry mulching ensures minimal environmental impact while achieving land management goals. Thanks for highlighting these important benefits!

This is a fantastic read! Small clearings in forests play such a vital role in promoting biodiversity and improving overall forest health. They provide opportunities for new plant growth and create habitats for various wildlife species. In the land clearing industry, incorporating sustainable practices like selective clearing can balance land use with ecological preservation. Thanks for highlighting these benefits!

This is a fantastic article! Small clearings are such an effective way to promote biodiversity and improve forest health. By creating space for new growth and encouraging diverse ecosystems, small clearings support sustainable forest management. Thanks for sharing these insightful benefits of small clearings!

Great initiative! Sustainable land clearing practices are changing the way we prepare land for future use, focusing on safety and precision.

This article highlights the valuable role that small clearings play in forest health and biodiversity. It’s fascinating to see how mimicking natural forest processes can enhance wildlife and plant life in managed forests. The increase in bird varieties and shrubs like red currant and salal really shows how such clearings foster a rich ecosystem.

Great insights into the role of arborists! This post does a fantastic job explaining their importance in maintaining healthy trees and landscapes. It’s a must-read for anyone who cares about their greenery!