2020 Reforestation Project: Year 2 Report

This article is part of the Hanson Family Forest series.

In January 2020 we planted 18 acres on our family’s land near Bucoda, WA in an effort to restore several degraded sites that had been logged by a previous landowner, but not replanted. These were challenging sites to recover as they were comprised of either dense brush, Himalayan blackberry, mixed grasses, a smattering of naturally regenerated hardwoods, thin or compacted soils, or any combination of these conditions. The site preparation and planting strategy we used is summarized in an earlier blog, Raising 5,200 Children by Shovel and Machete, so I will not rehash that here. However, now that these seedlings are poised to go into their third growing season, it’s instructive to look at how the seedlings are faring and how the site is recovering from the initial site preparation methods.

Cut to the Chase

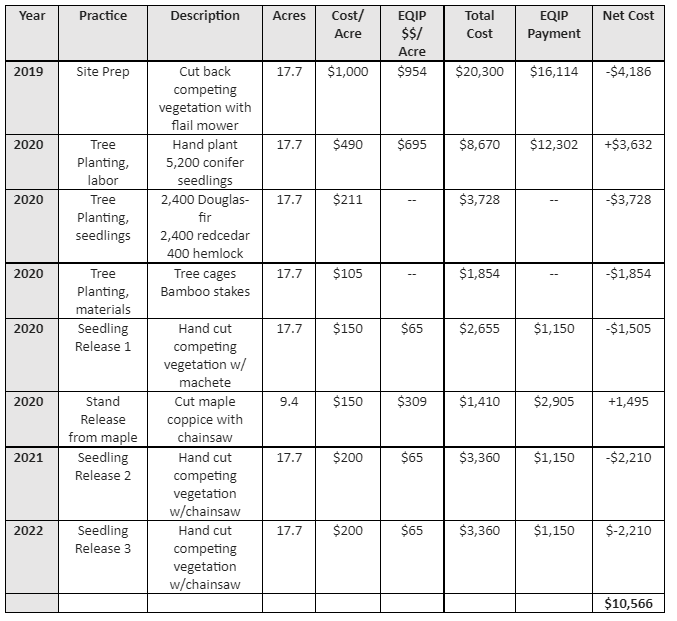

If you want to avoid the blah, blah, blah that follows and cut to the logistics and costs of the project to date, here you go. For those of you who like the details, please read on…

A Brief Recap of 2020

Prior to planting, the dense brush was cut to ground level using a flail-mower attached to a mini-excavator. Some selective pre-commercial thinning occurred across the low overstory of naturally regenerated red alder, bigleaf maple, cherry, and cascara. No other site preparation, other than mowing the existing understory growth and groundcovers, was used. Conifer seedlings were planted at approximately 350 trees per acre (TPA) at the beginning of January 2020, and included a combination of Douglas-fir, western redcedar, and western hemlock. The redcedar were caged with mesh tree protectors.

A combination of Douglas-fir and redcedar were planted across the most open and exposed sites, and a combination of western hemlock and redcedar were planted in the shadier sites and down into the steeper ravines and valleys along the northern side of the property.

Holy Shrubberies, Batman!

Since we only cut the existing shrub layer back to ground level, essentially converting the above-ground vegetation to a coarse mulch, and left the roots intact, nearly the entire chorus of shrubs grew back with a vengeance the following spring. What I found most interesting was observing which shrubs recovered with the most vigor, and which are took longer to regrow. Red elderberry and Himalayan blackberry have been the two most impressive specimens so far, and cutting them back only seemed to make them angry. The elderberry threw up tall fingers of straight, rigid green stems nearly six feet high from each of their stumps, and opened defiant compound leaves that hungrily captured the sunlight. The blackberry pushed out arching canes in every direction of the same length, and popped out a blur of prickly leaves.

Given the abundance of both of these species across the planted areas, they nearly recolonized the entire low canopy of the understory, and immediately began outcompeting the planted conifer seedlings for light. Sword fern also unfurled a new crown of fronds in the late spring, but the new growth was stunted and didn’t achieve the same height or spread of the prior plants. However, I suspect its growth will become more robust each year henceforth. The shrubs that are taking longer to recover tend to have woodier stems, and include: salmonberry, vine maple, Oregon grape, and salal.

Man vs Nature

When we observed the immediate and rapid response of the shrub layer during the first spring following planting, my family immediately set to it in mid-March with machetes and a sense of optimism and manifest destiny. The grandparents were called down on regular weekends, the kids were unleashed with sharp tools, and we were able to make a pass through nearly the entire 18-acre plantation by May.

With a crew of three or four of us we cut back all encroaching vegetation within a two-foot radius of each seedling at the rate of about an acre per hour. I paid the kids for their time (half always goes in the bank for college) using the EQIP funds we received for the first year of competing vegetation control following planting ($65/acre), and this provided a lucrative incentive that garnered their attention span throughout the duration of the project.

When we finished by early May I was astounded we had covered nearly the entire planting area. It was a remarkable achievement and I felt personally gratified that we were able to accomplish the task ourselves. There was much congratulating of one another, a general cheer went up, someone may have done the happy dance. And it was all for naught…

Re-enter the Dragon

On a routine monitoring expedition in mid-May it quickly dawned on me that our efforts had been entirely futile. When I returned to the first planting site where we initially began cutting back the new growth in mid-March, that same vegetation had continued to grow, and by mid-May we could hardly tell we had ever been there. The plants had another two months of growing conditions to throw up a new round of growth and erase the progress we had made.

I despaired. It was not tenable to leave these sites for another year and come back to treat them again the following spring. Even in mid-May it was highly likely the plants would have an additional month-and-a-half to put on yet more growth. If we didn’t return to treat the sites until mid-to late spring the following year, it would be nearly impossible to find the seedlings, and many would languish under the newly forming canopy of leaves over them. It was time to call in the professionals.

The Right Tool for the Job

Shortly after the traumatic monitoring visit in mid-May I contacted Miguel Torres at Torres Reforestation, who had conducted projects for other small woodland owners in the area and came highly recommended. Miguel came out and reviewed the seedling release project. I also asked him to look over a 9.5-acre Douglas-fir plantation that was planted by the previous landowner in 2018 and was being menaced by an emerging mob of sprouting maple stumps. We settled on a price of $150/acre for both the seedling release and cutting of the maple coppice, and Miguel’s crew arrived in mid-June and within two days had completed both tasks. My family is endeavoring to avoid the use of herbicides in our forests, so Miguel’s crew used machetes and large brush hooks to clear the competing vegetation away from the seedlings, and a chainsaw to cut the sprouting maple stems.

During the first growing season the majority of the conifer seedlings put on a flush of new green needles, but not much appreciable height or lateral growth. All their resources were going into growing roots and adapting to a foreign soil. Given the lack of vegetative growth, the tree cages did not need to be lifted in order to protect the leaders of the trees from browsing animals. I asked the crew to reach down in and straighten any seedlings that were bent over when the cages were originally installed, but that was the sole seedling/cage maintenance activity.

Miguel informed me that, in retrospect, he had underbid the project, and that $150/acre did not cover the full cost of his and his crew’s time. He honored our original agreement, but let me know that he would need to charge more in following years. As I stated earlier, our EQIP contract provided $65/acre for the seedling release, so we incurred some out-of-pocket expense for that project. However, EQIP also provided $309/acre for the cutting of the maple coppice, so we were able to use some of the remaining funds from that project to offset the out-of-pocket expense of the seedling release.

Cutting back the new spring growth in mid-June provided the perfect timing to control future growth of competing vegetation. The main phase of spring growth had ebbed, and there was little vigor remaining in the roots of the shrubs to fuel much additional growth that year.

Fast forward 12 months and we had Miguel and his crew come back again in June of 2021 to cut back the competing vegetation that had grown back the spring of that year. This time Miguel’s crew used chainsaws to clear vegetation within immediate proximity of each seedling. Miguel charged by the hour this time, and his costs were higher than the previous year, twice as high, totaling an average of $300/acre. The spring of 2021 saw remarkable height growth to many of the tree seedlings, so we also had the crew lift the cages to protect the terminal leader of each young tree from deer browse.

Fast forward nearly another 12 months and we’ve just entered 2022 and are on the cusp of another year of growth – both for the conifer seedlings and the brush and blackberry. We will have Miguel’s crew return in June again for a third year of seedling release, after which time I expect the tree seedlings will begin reaching a free-to-grow height above the majority of the surrounding brush. We’ll have to keep an eye on the blackberry, however, as it has the tendency to use young saplings as scaffolding and can pull them down or deform them as it clambers its way up their branches. Shortly after Miguel’s crew has finished their work we will also conduct a seedling mortality survey to see how successful our reforestation has been. As long as we have at least 200 well-distributed trees per acre, I will consider the project a success. I’ll report back after that survey with the findings.

Leave a Reply