Women in the Woods: Then and Now

Just as it would be wrong to only tell your mother you love her on Mother’s Day, it is a mistake to only pay tribute to the contributions of women to forests and forestry once per year.

But here we are at the beginning of National Women’s History Month, this Sunday is International Women’s Day (March 8th), and it feels like the right time to shout from the rooftops how important women are to sustaining healthy forests. That fact doesn’t change when March ends — so we promise not to stop shouting it!

The forestry sector in the United States has historically been dominated by men and Paul Bunyan-style masculinity. Prior to the 20th century, women passionate about wildlife and conservation causes were largely limited to invisible action from the sidelines. There were of course exceptions, women whose names and contributions we remember today. Harriet Hemenway and Minna B. Hall come to mind, founders of the first ever Audubon Society in Massachusetts; so does Maria Sanford, who led the Minnesota Federation of Women’s groups in their efforts to protect 400,000 acres of forestlands that eventually became Chippewa National Forest.

When the U.S. Forest Service was established in 1905, Victorian era beliefs about the place of women in society still reigned.

Female employees were mostly relegated to secretarial and administrative work.

Then came Hallie M. Daggett, the first field officer employed by the Forest Service. When she applied for an open fire lookout position in 1913, her two male competitors were totally unfit for the job. The supervisor in charge, McCarthy, obviously thought he’d found himself between a rock and a hard place.

He wrote of Hallie, “This individual has all the requisites of a first-class Lookout…The novelty of the proposition which has been unloaded upon me, and which I am now endeavoring to pass up to you, may perhaps take your breath away, and I hope your heart is strong enough to stand the shock.

“It is this: One of the most untiring and enthusiastic applicants which I have for the position is Miss Hallie Morse Daggett, a wide-awake woman of 30 years, who knows and has traversed every trail on the Salmon River watershed, and is thoroughly familiar with every foot of the District. She is an ardent advocate of the Forest Service, and seeks the position in evident good faith, and gives her solemn assurance that she will stay with her post faithfully until she is recalled. She is absolutely devoid of the timidity, which is ordinarily associated with her sex as she is not afraid of anything that walks, creeps, or flies.”

Despite the risk to Mr. McCarthy’s heart, Hallie was awarded the position. She served as Fire Lookout on Klamath Peak in Klamath National Forest in California for 4-7 months per year for fourteen years. We have no doubt many more women of the time would have served such wilderness posts as faithfully, had they been given the chance.

The Forest Service has come a long way, as has the world of forestry in general, in recognizing women as able foresters.

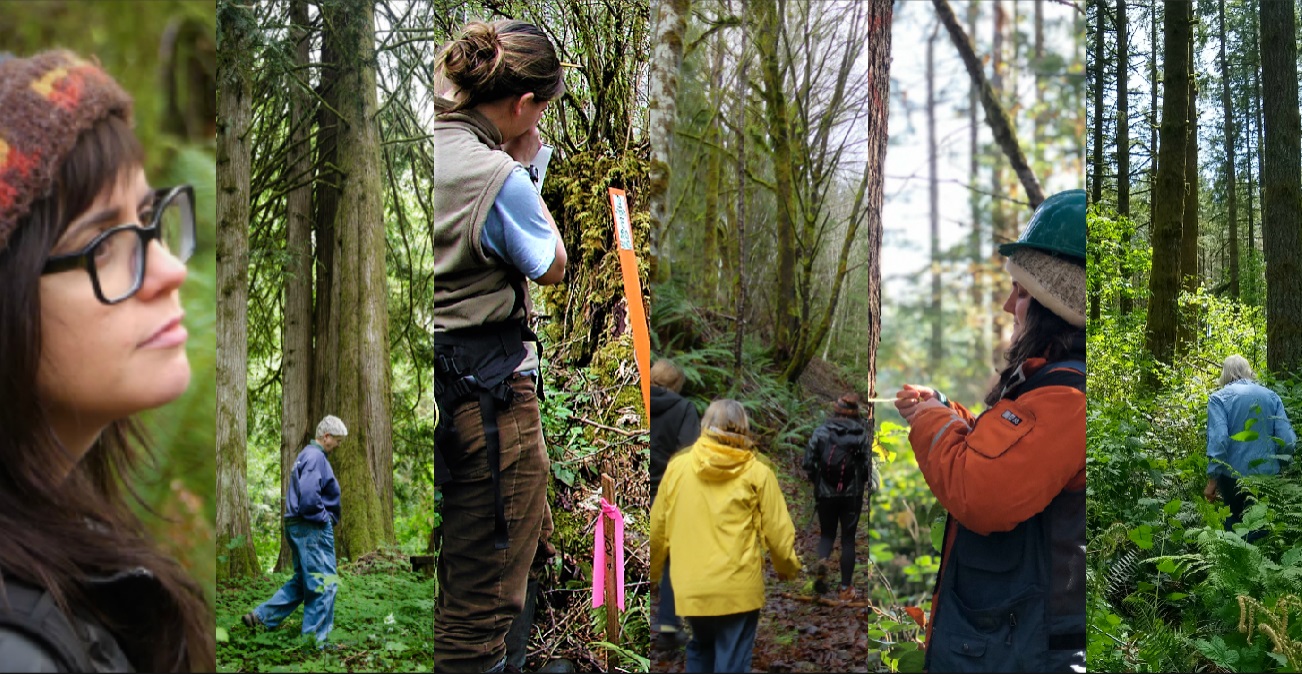

Women are doing more research on forests, more fieldwork in forests, and making more decisions for forests than they ever have.

NNRG is proud to be a part of this change movement. Over half our staff are women, including Director of Programs Rowan Braybrook, Forester Marcia Rosenquist, Finance Director Karen Gray, Forestry Technicians Teodora Rautu and Jane Frazee, and Outreach Coordinator Alex Dolk. (Not to mention a few former awesome women staff: Lindsay Malone and Jose Narvaja.) NNRG’s board President is Christine Johnson, whose 10-acre, FSC®-certified forest on Waldron Island is a living testament to her stewardship and love of the woods. 74% of NNRG’s member group of family forests are owned solely or partially by women.

According to the National Woodlands Owners Survey (NWOS) in 2018, women were the primary owners of 30% of woodlands over 10+ acres in Washington, and 36% of woodlands of 10+ acres in Oregon. Of course, the number of women who are stewarding woodlands is just one indicator of gender parity in the field of forestry. It doesn’t tell you whether women have the same resources, forestry knowledge, opportunities, and social capital as their male counterparts.

A study of forest landowner offspring conducted for the National Association of State Foresters showed that 83% of women sampled were interested in managing their family’s forestland when the transfer occurred, but only 34% felt they had enough knowledge to make forest management decisions. According to the USDA 2007 Agriculture Census, women who own or manage forests and farms tend to have smaller parcels, lower average sales, and are less likely to attend educational events or be aware of assistance opportunities.

That’s where the Women Owning Woodlands Network, aka WOWNet, comes in.

WOWNet is a consortium of state-wide groups that develop programming and distribute knowledge specially targeting women woodland owners in their regions.

The programs “…allow women to come together to learn about forest management, share their forestry and natural resources experiences, and exchange personal knowledge in a unique peer-to-peer learning environment,” according to the Oregon chapter’s website. Dozens of WOWnet workshops are offered around the U.S. every year.

“Something we hear from our women consistently that makes WOWNet unique from all the other programming out there is that we build in time for the women to learn and share from each other,” says Tiffany Hopkins, Coordinator of Oregon’s WOWNet, which is managed through OSU’s Forestry and Natural Resources Extension.

“We offer this space that allows women to share their thoughts and questions that they may not feel as comfortable bringing up in mixed-gender audiences,” says Hopkins.

Hopkins says a critical forestry skill many women seem to want to learn in a friendly environment is chainsaw safety and maintenance. She says she can’t offer enough of these classes to keep up with demand. This makes some sense, as power tools are traditionally seen as a masculine interest. And, according to Hopkins, some women are frustrated by the sort of chainsaw advice they’ve gotten from the men close to them. “They say specifically, ‘My husband tried to teach me but he doesn’t get it!’”

WOWnet’s blog includes a post titled ‘Chainsaw Safety & Comfort: Tips & Tricks for Women.’ It includes suggestions for picking the right chainsaw for your size, the ergonomics of using the saw, weary safety gear that fits you properly, and keeping hair, undergarments, and jewelry out of the way during operation. It’s probably one of the only examples of where the practical advice for women differs a little bit from what men might receive, says Tiffany. For most other workshop subjects, the material covered is pretty much the same ― the only difference is that the learning environment may seem more welcoming.

Lynn Baker co-owns Cedar Row Farm, which is nestled in the Nehalem River foothills in Oregon, with her wife Eve Lonnquist and Lonnquist’s two brothers.

The farm was purchased 101 years ago by Lonnquist’s grandmother, who planted its namesake row of cedars. Cedar Row Farm is a member of the Oregon Woodland Cooperative, and Baker is on the boards of the Oregon Woodland Cooperative and the Columbia County chapter of the Oregon Small Woodlands Association.

Baker said that there are certainly differences in how she and her wife approach stewarding their forest compared to some of their neighbors and friends. But they come not so much from gendered perspectives as from individual personalities and philosophies. “We choose to not use chemicals because we feel that’s environmentally not a good idea. Other people choose to because they feel it’s necessary to keep weeds and invasive species out. So philosophically we’re not on the same page but at the end of the day we’re all hoping to do the right thing for our farm.”

Elona Krafton owns Two Frog Bog, a 20-acre forest situated in the Rainier foothills just outside of Roy, Washington. Elona manages the AirBnb units (including a beautiful yurt!) on the property.

Krafton doesn’t think being a woman has necessarily influenced how she approaches stewarding her forest. “I have my little 20-acre forest and it’s not a lot to do.” But she thinks it helped her obtain EQIP funding from the Natural Resources Conservation Service a few years ago. She received cost-share assistance for monitoring, protecting, and enhancing the wetland on her forest.

While NRCS does offer special financial assistance incentives to Historically Underserved Producers, this no longer applies to women. They say on their website, “Gender alone is not a covered group for the purposes of NRCS conservation program authorities.”

Forester Marcia Rosenquist joined NNRG in January of this year. She thinks being a woman hasn’t really influenced her work experience lately ― but that hasn’t always been the case.

“It was more of an issue when I was an arborist and working on construction sites. Being a woman when the crew is used to a man taught me to walk a fine line between assertive and friendly. I learned to be nice, but not too nice, and loud when I needed to be.”

“I’ve been fortunate that in my forestry work I haven’t had any of these same types of experiences.”

It’s clear we’ve made enormous strides in closing the gender gap so long present in forestry. What’s left to work on?

Tiffany Hopkins thinks part of the goal might include, paradoxically, women coming to WOWNet workshops a little less often.

“I’ve seen multiple examples of a woman who came to every single WOWNet event for a while, but then over the course of two years stopped coming so often and eventually stopped coming at all. Then I see her at other events ― like [forestry] conferences or Tree School ― and I see that as a success. Because now she has this confidence to not feel like she needs a women’s only group.”

Hopkins isn’t as concerned about the number of event attendees as she is about the experiences the events themselves provide.

“The stories of these women are so much more impactful than the numbers. There’s one story I like to tell to explain this: A woman came to one of my [WOWNet] events, a ‘Walk in the Woods’ that had been thrown together at the last minute. She brought a forest-owning friend with her who’d never been to a WOWNet event before. After the event, I was chatting with some of the attendees in the parking lot and the first-timer stayed to tell us her story.

“Her husband had passed away the previous year. He was the one who’d done all the forestry stuff, and she took care of the horses. Without her husband around she thought she’d have to let go of it all ― she didn’t know how she was going to take care of this forest.”

Two of the other women in the group had also lost their husbands and were managing their forests on their own. Hopkins says meeting fellow forest owners who’d had the same experience changed the woman’s mind about her prospects.

“She started crying and was so, so grateful. It was a special and empowering experience.”

We’ll end with this: we can probably all agree that striving for more special and empowering experiences in forestry ― for everyone ― is a worthy goal.

We’re interested to hear from our readers on this subject. Do you think gender plays a role in your experience in the world of forestry? Let us know here.

Leave a Reply